Counting Stairs

Around August 2021, I had the fortune, through whatever assortment of searches I had been doing, to be invited to participate in Google’s “Foobar” coding challenge. I completed all of the puzzles, never heard anything else, and that was that. However, one question was particularly intriguing, and it has stuck with me. It was called “The Grandest Staircase of Them All”. It went as follows.

Problem Statement

With the LAMBCHOP doomsday device finished, Commander Lambda is preparing to debut on the galactic stage – but in order to make a grand entrance, Lambda needs a grand staircase! As the Commander’s personal assistant, you’ve been tasked with figuring out how to build the best staircase EVER.

Lambda has given you an overview of the types of bricks available, plus a budget. You can buy different amounts of the different types of bricks (for example, 3 little pink bricks, or 5 blue lace bricks). Commander Lambda wants to know how many different types of staircases can be built with each amount of bricks, so they can pick the one with the most options.

Each type of staircase should consist of 2 or more steps. No two steps are allowed to be at the same height - each step must be lower than the previous one. All steps must contain at least one brick. A step’s height is classified as the total amount of bricks that make up that step.

For example, when N = 3, you have only 1 choice of how to build the staircase, with the first step having a height of 2 and the second step having a height of 1: (# indicates a brick)

#

##

21

When N = 4, you still only have 1 staircase choice:

#

#

##

31

But when N = 5, there are two ways you can build a staircase from the given bricks. The two staircases can have heights (4, 1) or (3, 2), as shown below:

#

# #

# ##

## ##

41 32

Write a function called solution(n) that takes a positive integer n and returns the number of different staircases that can be built from exactly n bricks. n will always be at least 3 (so you can have a staircase at all), but no more than 200, because Commander Lambda’s not made of money!

Disclaimer

Plenty of other people have already dissected this problem and offered their own solutions. I’m not pretending to break any new ground here but just go over some of my thoughts on it.

Brute Force

The easiest starting point is to manually figure out the solutions for low values of n and look for a pattern. The problem statement provides the solution for values of 3, 4, and 5. While drawing the blocks is useful for visualization purposes, the numbers beneath them are the only necessary bits. So, you start getting something like this:*

| # of Blocks | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| # of Steps | 2 | 12 | 13 | 14 23 | 15 24 | 16 25 34 | 17 26 35 | 18 27 36 45 | 19 28 37 46 |

| 3 | 123 | 124 | 125 134 | 126 135 234 | 127 136 145 235 | ||||

| 4 | 1234 | ||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

From this table, a few observations immediately arise, which may or may not be useful:

- The number of entries for the row with two steps increases by one every time there’s an odd number of blocks.

- The total kind of looks like the Fibonacci Sequence. Maybe it’s recursive.

- The maximum number of steps corresponds with the triangle numbers: 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, …

- For a given number of blocks and steps, the possible partitions can be derived iteratively by starting with a bunch of small steps and one large step, and then moving one block at a time from the large step to the smaller ones until you get stuck.

Getting Mathy

Thanks to the Neil Sloane videos on the Numberphile channel on YouTube, I knew about the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS). As it turns out*, the sequence I wrote down can be found there. It’s A111133, Number of partitions of n into at least two distinct parts. The first formula on that page points back at A000009, Number of partitions of n into distinct parts. The difference between these two sequences is literally 1, as the latter corresponds to relaxing our problem statement to allow staircases with a single stair.

At this point, we could certainly start going down the rabbit hole of things like integer partitions or partition functions, but for now, let’s stick to the task at hand. The first formula on the A000009 page is

G.f.: Product_{m>=1} (1 + x^m) = 1/Product_{m>=0} (1-x^(2m+1)) = Sum_{k>=0} Product_{i=1..k} x^i/(1-x^i) = Sum_{n>=0} x^(n*(n+1)/2) / Product_{k=1..n} (1-x^k)

The “G.f.” part stands for generating function and is the left side of the equation below. Pulling out just the first expression and formatting everything nicely, we have

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} q(n)x^n = \prod_{k = 1}^\infty (1 + x^k) \]

Okay, but what does this actually mean? Well, multiplying out the first few terms of the product and simplifying, we get the following:

\[ 1+1x+1x^2+2x^3+2x^4+3x^5+4x^6+5x^7+6x^8+\ldots \] The nth term of the sequence (including 0) corresponds to the coefficient associated with the value of xn. So, the solution to our problem for n=8 is 6 (ignoring the minus 1 for now). And this makes sense, since before multiplying and adding up the x8 terms, we had

\[ x^8+xx^7+x^2x^6+x^3x^5+xx^2x^5+xx^3x^4 \]

which are the same values as seen the table. Through all of this multiplication, every possible distinct partition is hit once, and summing them up gives the total. We know that every distinct partition is hit exactly once, since each time we multiply by (1 + xk) the 1 preserves everything that already exists, and the xk, which is the largest term seen thus far, adds the new components. Because xk never repeats, neither do any components of a partition (e.g., there’s no way to get an x4x4 term).

Into Code

Setting things up in table form, we’ll leave aside the powers of x for now and just focus on the coefficients. Let’s see how the (1 + xk) process plays out. In this form, the process can be thought of as leaving a copy of the current coefficients where they are, shifting another copy over by a value of k, and adding them together.

| n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k=1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| k=2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| k=3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| k=4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| k=5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| k=6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| k=7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| k=8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 13 |

| k=9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 21 | 22 |

| k=10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 27 | 29 | 31 |

| k=11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 35 | 39 |

| k=12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 17 | 20 | 24 | 27 | 31 | 36 | 40 | 45 |

| k=13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 25 | 29 | 33 | 39 | 44 | 50 |

| k=14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 26 | 30 | 35 | 41 | 47 | 54 |

| k=15 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 31 | 36 | 43 | 49 | 57 |

| k=16 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 37 | 44 | 51 | 59 |

| k=17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 45 | 52 | 61 |

| k=18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 46 | 53 | 62 |

| k=19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 46 | 54 | 63 |

| k=20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 38 | 46 | 54 | 64 |

A few observations:

- At each step, the sequence is symmetrical (except for where it’s truncated in the table).

- Coefficients in the table only ever affect values to their right; never to their left. (There’s no harm in truncating the table to just the coefficients we’re interested in.)

- Upon reaching the kth step, the solution for that value of n has settled into place.

- The number of non-zero coefficients grows by the step number.

The first bullet is interesting but not relevant here, but the next two point to how this can be coded. It’s very short and is basically exactly what happens in the table, except instead of recording a new row, it just overwrites itself on every step.

def a000009(n):

arr = [1, 1] + [0] * (n - 1)

for i in range(2, n + 1):

arr[i:] = [x + y for x, y in zip(arr, arr[i:])]

return arr[-1]

In terms of performance, I’d like to think this is pretty good. It preallocates the list to the exact size needed, though that’s somewhat of a micro-optimization. On the other hand, with regard to the last bullet above, it sometimes iterates unnecessarily through the part of the list (the empty entries in the table), but that’s only for a few steps. Overall, given the nested for loops and fixed size, we can say that the time complexity is O(n²), and the space complexity is O(n). Without resorting to NumPy, we might also get a slight improvement by updating the list in reverse order to do so in-place and avoid using slices.

def a000009(n):

arr = [1, 1] + [0] * (n - 1)

for i in range(2, n + 1):

for j in range(n, i - 1, -1):

arr[j] += arr[j - i]

return arr[n]

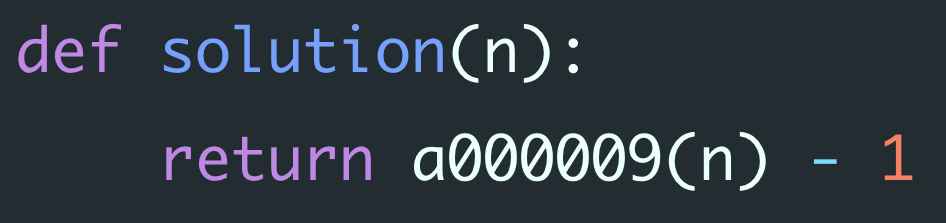

To get the final solution of the original problem, of course, don’t forget to subtract 1.

def solution(n):

return a000009(n) - 1