Grissom Controls

TL;DR: Here’s an article I wrote for the ASHRAE Journal.

I studied civil engineering at Purdue, and within that, I focused on architectural engineering, which deals with building systems. This includes things such as lighting, the building envelope (e.g., windows and insulation), and especially heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC). Near the end of my senior year, I needed a summer job before starting grad school in the fall. I approached the Vice President for Physical Facilities after a presentation of his, he passed on my information, and I managed to get a job within the energy group*.

Poking Around Building Automation Systems

Without a specific plan for me within the group, I was left to just poke around the automation systems that controlled the HVAC systems on campus, looking for ways to improve energy efficiency. Half of the buildings used Siemens, which was hard to understand, and I ignored*. The other half, generally the newer systems, used WebCTRL, which was more of a node graph, with boxes and wires representing the various sensors and logic components. I quickly picked this up, and though I wasn’t empowered personally to make changes to the system, I developed recommendations that I passed on to the techs for implementation.

Some of my recommendations were very basic, such as adjusting minimum ventilation requirements in offices. Some were fancier, such as changing the control scheme of the various dampers at the air handler to minimize how quickly the fans needed to run. One had immediate impact, as students were passing out in the new choir building, and I noticed that CO2 levels were literally off the charts (above 1500ppm, maybe even above 2000ppm) due to a lack of ventilation, despite the system trying to bring in as much as it could. This led to the discovery of a filter completely clogged with construction dust, and after it was replaced, things returned to normal.

The Birth of Grissom Controls

One piece of logic I noticed in a newer building* was used to adjust the amount of required ventilation based on what was happening in the individual zones. This logic came from Appendix A of the ASHRAE 62.1 standard, which concerns ventilation for commercial buildings. It has to do with the idea that the different zones might all have different ventilation needs, but the supply air has a given percentage of outside air and can’t precisely match those needs. So, you look at the needs of the most critical zone and then adjust for the fact that some of the return air from the non-critical zones is unvitiated (i.e., has unused ventilation air), and you can claim credit for it as it’s recycled. As I learned about this, I first had the techs fix a sign error in the calculation, but I also realized something fundamental: increasing the airflow to certain zones in the building can reduce the outside air requirement, and by doing so, the building’s overall energy consumption might be reduced.

Increasing the amount of airflow to a zone comes with an energy penalty, however, due to needing to heat that air in order to avoid overcooling the space. So, this led to an optimization problem that became the focus of my work. Fortunately, WebCTRL had a Simple Open Access Protocol (SOAP) interface that I could use to pull data into Excel. There, I could model energy consumption in the building and ask the Solver add-in to try to minimize it. Unfortunately, though, the problem is both nonlinear and can get rather large, especially in buildings with dozens of zones. So, Solver can quickly get overwhelmed. Long-term, it also didn’t seem feasible to try to control a building from a spreadsheet. Now, WebCTRL itself had a microblock that you could write custom code in, and while it would solve the software integration problem, it didn’t seem up for the scale of the task. Thankfully, WebCTRL also had the ability to run add-ons written in Java. Except since I didn’t know Java, that became my Christmas break project*.

At some point I started calling the project Grissom Controls, named after the building* on campus, which itself was named after the astronaut. In the spring semester of my grad year, then, I took three credit hours of research to be able to claim this toward my non-thesis master’s. As I had also done an entrepreneurship certificate as an undergrad and had been attending Foundry Grounds and other events put on by the entrepreneurship and commercialization folks, I began to think that maybe this project could become a company outright. I also convinced my team in a civil engineering business course to use this as our business plan idea.

My first implementation of the WebCTRL add-on used a particle swarm optimization algorithm to try to find the minimum energy consumption, which seemed to work okay but sometimes produced wildly different answers, depending on the starting conditions and whether the particles got caught in a local minimum. After enough nights pondering the problem in bed, I came up with an algorithm that reduced the search space to just two variables and could be solved with just a grid search.

Commercialization?

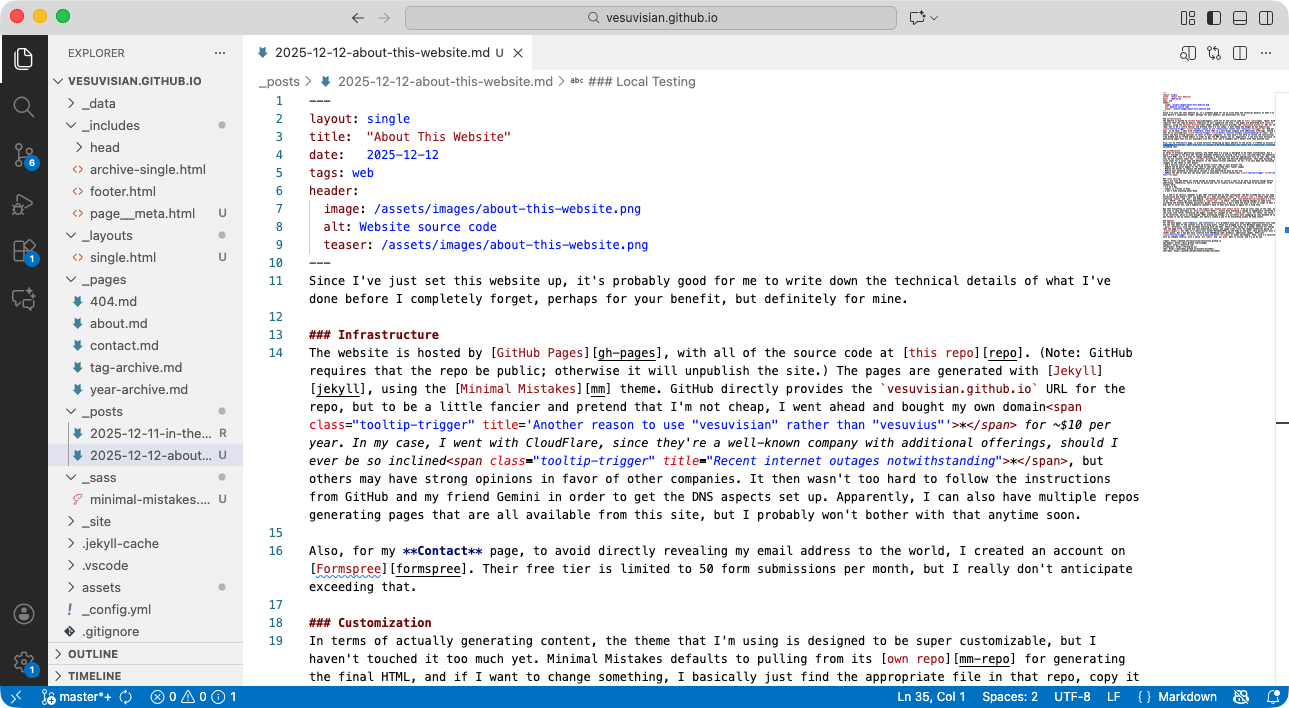

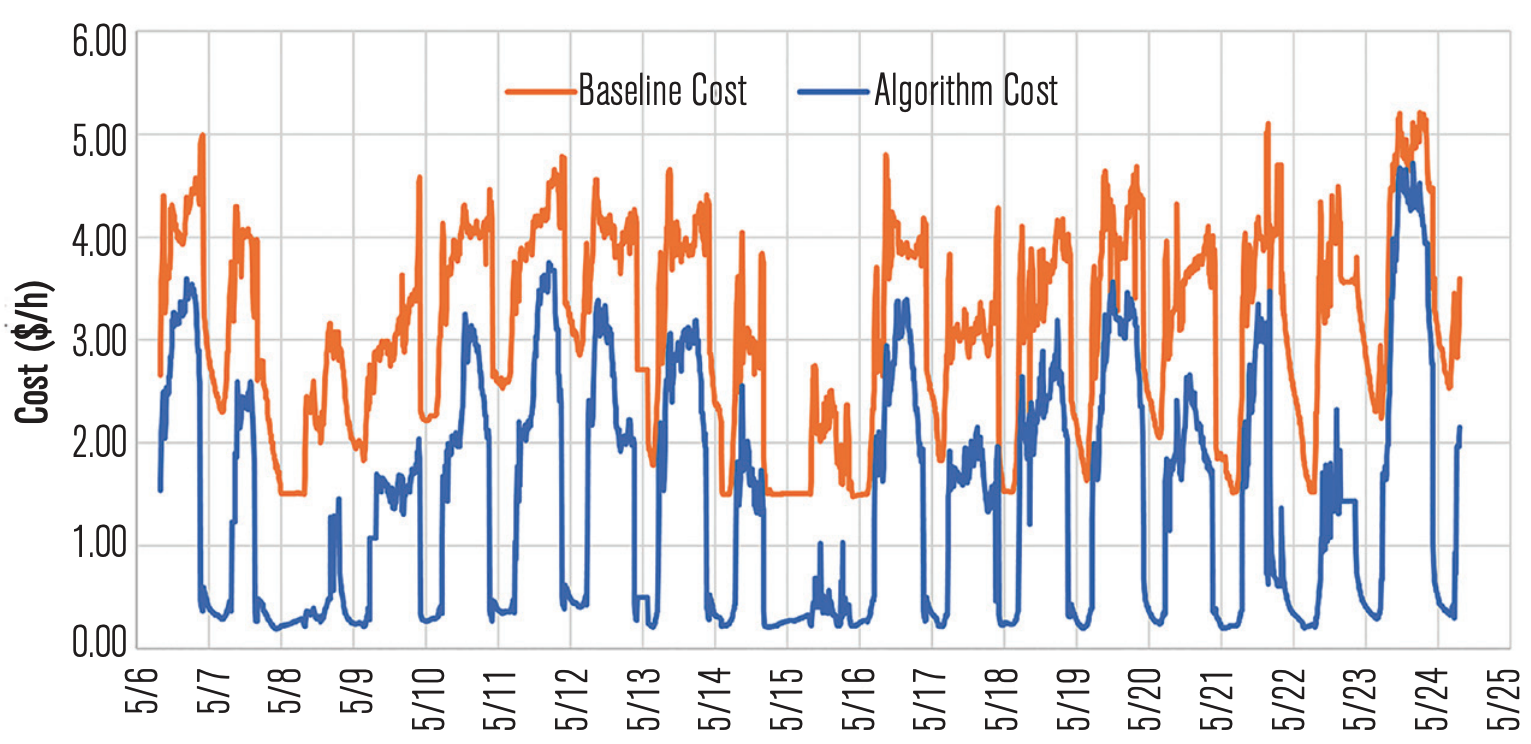

Near the end of the school year, I entered and won the Schurz Innovation Challenge, presenting the problem and algorithm to a non-technical audience, and I started leaning more heavily into the idea of commercialization. I stuck around for another year to get an MBA and continued working part-time for Physical Facilities. During this time, I continued to improve the code and spoke with the makers of WebCTRL about it. Though I wasn’t yet allowed to run the add-on “live” (actually controlling a building), I could run it in a “ghost” mode, collecting data and calculating the actual costs versus the optimized costs, as seen in this chart, for example.

During this particular testing period, the algorithm showed a potential 70% reduction of hot water consumption, 42% for chilled water, and 53% for electricity, leading to an overall operating cost savings of 54%.

Unfortunately, graduation occurred before I was able to get algorithm fully up and running. I created an LLC and signed a license agreement with the university to be able continue working on it, but I moved out to Washington, DC for a full-time job. Without real systems to use, progress slowed down, though I was able to do some limited testing at the University of Virginia. In the hope of other building automation companies potentially being interested in picking this up, I decided to write about it for the ASHRAE Journal, which is the trade publication for the HVAC industry. It took over a year to get through review but eventually made it into the August 2022 issue, and you can find it here. It discusses the problem and algorithm in more technical detail but leaves the solution just vague enough to avoid direct recreation.

At some point, I may publish the original Java or more recent Python version of the algorithm under something like an AGPL license, but in the meantime, if you are a building automation professional, feel free to reach out.

PS: The header image on this page is the logo that I created for Grissom Controls. It was somewhat inspired by the Johnson Controls logo and can be thought of as a Venn diagram with cooling, heating, and either sustainability or ventilation.